How does iptables work?

other link:

iptables is just a command-line interface to the packet filtering functionality in netfilter. However, to keep this article simple, we won’t make a distinction between iptables and netfilter in this article, and simply refer to the entire thing as “iptables”.

The packet filtering mechanism provided by iptables is organized into three different kinds of structures: tables, chains and targets. Simply put, a table is something that allows you to process packets in specific ways. The default table is the filter table, although there are other tables too.

Again, these tables have chains attached to them. These chains allow you to inspect traffic at various points, such as when they just arrive on the network interface or just before they’re handed over to a process. You can add rules to them match specific packets — such as TCP packets going to port 80 — and associate it with a target. A target decides the fate of a packet, such as allowing or rejecting it.

When a packet arrives (or leaves, depending on the chain), iptables matches it against rules in these chains one-by-one. When it finds a match, it jumps onto the target and performs the action associated with it. If it doesn’t find a match with any of the rules, it simply does what the default policy of the chain tells it to. The default policy is also a target. By default, all chains have a default policy of allowing packets.

Tables

As we’ve mentioned previously, tables allow you to do very specific things with packets. On a modern Linux distributions, there are four tables:

- The filter table: This is the default and perhaps the most widely used table. It is used to make decisions about whether a packet should be allowed to reach its destination.

- The mangle table: This table allows you to alter packet headers in various ways, such as changing TTL values.

- The nat table: This table allows you to route packets to different hosts on NAT (Network Address Translation) networks by changing the source and destination addresses of packets. It is often used to allow access to services that can’t be accessed directly, because they’re on a NAT network.

- The raw table: iptables is a stateful firewall, which means that packets are inspected with respect to their “state”. (For example, a packet could be part of a new connection, or it could be part of an existing connection.) The raw table allows you to work with packets before the kernel starts tracking its state. In addition, you can also exempt certain packets from the state-tracking machinery.

In addition, some kernels also have a security table. It is used by SELinux to implement policies based on SELinux security contexts.

Chains

Now, each of these tables are composed of a few default chains. These chains allow you to filter packets at various points. The list of chains iptables provides are:

- The PREROUTING chain: Rules in this chain apply to packets as they just arrive on the network interface. This chain is present in the nat, mangle and raw tables.

- The INPUT chain: Rules in this chain apply to packets just before they’re given to a local process. This chain is present in the mangle and filter tables.

- The OUTPUT chain: The rules here apply to packets just after they’ve been produced by a process. This chain is present in the raw, mangle, nat and filter tables.

- The FORWARD chain: The rules here apply to any packets that are routed through the current host. This chain is only present in the mangle and filter tables.

- The POSTROUTING chain: The rules in this chain apply to packets as they just leave the network interface. This chain is present in the nat and mangle tables.

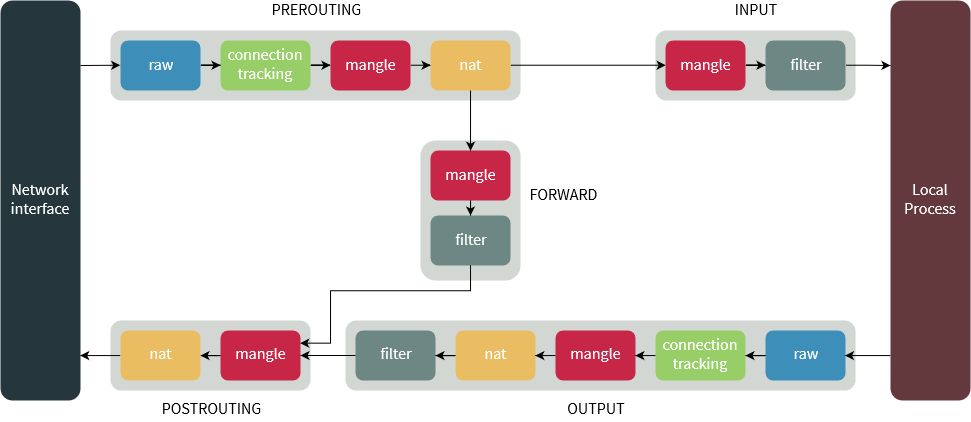

The diagram below shows the flow of packets through the chains in various tables:

Targets

As we’ve mentioned before, chains allow you to filter traffic by adding rules to them. So for example, you could add a rule on the filter table’s INPUT chain to match traffic on port 22. But what would you do after matching them? That’s what targets are for — they decide the fate of a packet.

Some targets are terminating, which means that they decide the matched packet’s fate immediately. The packet won’t be matched against any other rules. The most commonly used terminating targets are:

- ACCEPT: This causes iptables to accept the packet.

- DROP: iptables drops the packet. To anyone trying to connect to your system, it would appear like the system didn’t even exist.

- REJECT: iptables “rejects” the packet. It sends a “connection reset” packet in case of TCP, or a “destination host unreachable” packet in case of UDP or ICMP.

On the other hand, there are non-terminating targets, which keep matching other rules even if a match was found. An example of this is the built-in LOG target. When a matching packet is received, it logs about it in the kernel logs. However, iptables keeps matching it with rest of the rules too.

Sometimes, you may have a complex set of rules to execute once you’ve matched a packet. To simplify things, you can create a custom chain. Then, you can jump to this chain from one of the custom chains.

Blocking IPs

The most common use for a firewall is to block IPs. Say for example, you’ve noticed the IP 59.45.175.62 continuously trying to attack your server, and you’d like to block it. We need to simply block all incoming packets from this IP. So, we need to add this rule to the INPUT chain of the filter table. You can do so with:

Let us break that down. The

-t switch specifies the table in which our rule would go into — in our case, it’s the filter table. The -A switch tells iptables to “append” it to the list of existing rules in the INPUT chain. However, if this is the first time you’re working with iptables, there won’t be any other rules, and this will be the first one.

As you might have guessed, the

-s switch simply sets the source IP that should be blocked. Finally, the -j switch tells iptables to “reject” traffic by using the REJECT target. If you want iptables to not respond at all, you can use the DROP target instead.

Previously, we’ve mentioned that the filter table is used by default. So you can leave it out, which saves you some typing:

You can also block IP ranges by using the CIDR notation. If you want to block all IPs ranging from 59.145.175.0 to 59.145.175.255, you can do so with:

If you want to block output traffic to an IP, you should use the OUTPUT chain and the

-d flag to specify the destination IP:

Listing rules:

Deleting Rules:

Flush all the INPUT rules

No comments:

Post a Comment